The Human Cost Behind the Olympics

The stadiums are built. The subways are in place. But one element of Beijing’s “preparation” for the 2008 Olympics has been less than glamorous: the dramatic intensification of the Party’s campaign to wipe out Falun Gong. Thousands have been arrested, hundreds have been sent to labor camps, and at least 12 have died in custody within a month of their detention. What other human costs remain hidden?

Ms. Chen Jiaolong went to work at Beijing’s Jinkui Decoration Factory as usual on January 24, 2008. But by evening, Chen found herself at Dongcheng District detention center after Chinese security agents raided the factory looking for Falun Gong practitioners.

A few months later, she was in Inner Mongolia, beginning a two year sentence of “re-education” at a labor camp in Hohhot.

Chen’s story is just one of thousands that Falun Gong adherents and their families have experienced since December 2007 as a systematic escalation of the campaign against the group has unfolded. She is one of dozens, and possibly hundreds, who have been sentenced to labor camps without a trial.

This escalation has taken place within a broader clean-up of “undesirables” that the Chinese Communist Party has embarked upon as it prepares for the Olympic Games in August 2008.

“It is increasingly clear that much of the current wave of repression is occurring not in spite of the Olympics but actually because of the Olympics,” said Amnesty International in a report released in April.

As has often been the case in recent crackdowns of this kind, Falun Gong adherents have quickly found themselves at the top of the “most wanted” list.

Official Policy Trickles Down

Indications that the Party would intensify the crackdown on Falun Gong in the run-up to the Olympics emerged as early as 2005. In November that year, Intelligence Online, a journal following developments within China’s security system, reported that the leadership had issued directives to intensify the campaign for fear that Falun Gong might spark a Ukraine-type “Orange” revolution.

“China’s deputy public security minister Liu Jing has been handed the job of stamping out the Buddhist-Taoist Falun Gong before the Olympic Games in 2008,” the article stated.

As the games drew closer, top officials began making public statements along similar lines. According to Amnesty International, in March 2007, Former Public Security Minister Zhou Yongkang issued an order in the context of “successfully” holding the Beijing Olympics stating: “We must strike hard at hostile forces at home and abroad, such as … the Falun Gong.”

Over the following year, reports of “Olympic security plans” and neighborhood meetings of relevant agencies began to emerge, as local actors explored how to carry out such directives.

According to one posting on the website of the government of Liulitun, a neighborhood of Beijing’s Chaoyang district [see image below], such a meeting was held in January 2008. It was attended by “Party secretaries and directors of ten communities.”

The highlight of the meeting was a speech by Chen Sumin of the 610 Office, an extra-legal task force charged with leading the campaign against Falun Gong.

“Each community should treat all work items of the 610 Office with a great sense of responsibility and importance, and not give Falun Gong practitioners any opportunities,” Chen emphasized in her speech, according to the site. “In particular, [we should] mobilize the power of the masses of residents, [asking them to] report promptly if they find anyone handing out [Falun Gong related] materials.”

To ensure such tasks are carried out wholeheartedly, and in line with common Party practice, incentives were then put in place.

In many cities a reward system was put in place offering money for identifying Falun Gong adherents to the authorities. For example, on July 11, Reuters reported that Beijing police were offering rewards of up to 500,000 yuan ($73,150) to people who provide tip-off s during the Olympics, among other targeted groups named was Falun Gong.

Large scale arrests

Though such measures appear to be primarily aimed at preventing Falun Gong adherents from distributing information about the discipline and abuses committed against its followers– a right guaranteed in China’s constitution–in practice, Chinese security agencies have been conducting door-to-door searches, detaining large numbers of people simply on the basis that they are known to be practicing Falun Gong.

According to reports from family and friends of those detained, a majority of arrests follow a common pattern. Officers from the local police station, Public Security Bureau (PSB) branch, or 610 Office come to an adherent’s home or workplace, conduct a search for any Falun Gong-related materials, and take the individual into custody at the district detention center.

“It was early in the morning when agents from the Public Security and State Security Bureaus came to my parents’ home in Hebei Province near Beijing,” says Si Yang, a computer consultant living in Los Angeles. “My sister was at work so they went there to pick her up. Then they searched the house and took my father and sister to a temporary detention center at a hotel.”

Once at the detention center, adherents face intense interrogation that often includes beatings, sleep deprivation, and in some cases, more severe forms of torture. The questioning is aimed at extracting both information about fellow practitioners and a commitment to cease practicing. The majority are still detained at such locations.

In several dozen cases, those detained have been sentenced to “re-education through labor camps” without trial, an option made possible because Chinese law allows sentencing for up to three years without the need to bring the accused before a judge. Indeed, available evidence indicates that the authorities have been taking advantage of the “efficiency” this procedure enables.

“After four days of interrogation, they released my elderly father, but within just a month, my sister was sentenced to one and a half years in a labor camp,” says Si. “She was deprived of sleep at the detention center and now we don’t know what her situation is because they won’t let my parents visit.”

The systematic nature of the arrests– and the fact that many victims had been detained or sentenced before for practicing Falun Gong–suggests that the authorities are using a previously compiled list of local adherents, a common PSB practice. According to former PSB and 610 Office agent Hao Fengjun, who defected to Australia in 2005, the authorities in the city of Tianjin, where he formerly worked, had a database of 30,000 Falun Gong practitioners’ names.

“Olympic” Geography of arrests

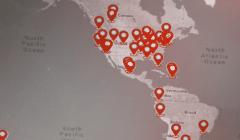

Not surprisingly, Beijing and its districts housing Olympic venues have been a particular focus of the campaign. In recent months, the Falun Dafa Information Center (FDI) has reported the names and details of 208 adherents detained in the city since December 2007; the Center has received information on dozens more arrests, but they lack sufficiently verifiable details to publish.

Of the 208 known to have been detained, 36 were from Chaoyang District, home to the Bird’s Nest and Water Cube, set to host the soccer and swimming events among others; 28 adherents were detained in Haidian District, site of the Beijing Olympic Committee headquarters as well as events such as basketball and volleyball.

Based on information received by the Center, by the end of June 2008, 30 Beijing residents who practice Falun Gong had been sentenced to labor camps–nearly 15 percent of those detained. The two central districts of Chaoyang and Haidian alone accounted for more than half of those cases.

More generally, at least one arrest of a Falun Gong adherent had been reported in each of the municipality’s districts and counties. As FDI spokesperson Gail Rachlin said in a recent release, such “artificially sterile, silent streets … should give visitors the chills.”

Deaths on the Rise

More chilling even than the increase in arrests and labor camp sentences has been the rise in the number of Falun Gong adherents reportedly dying as a result of abuse in custody–especially those dying within days, or even hours, of being detained by the authorities.

Within the first seven months of 2008, the Center had documented 12 cases of practitioner deaths occurring within less than one month of arrest and in some instances, within hours.

By comparison, in 2007, over the course of the entire year seven people died within such a short time in custody. In several of the cases this year, family members were able to view the body before its cremation and saw signs of torture, including strangulation marks or bruises from electric batons.

“The speed with which Falun Gong adherents are being seized by police, abused, and turning up dead is alarming and reprehensible,” says Rachlin. “These are people who never should have been arrested in the first place.”

One case that has garnered a particularly large amount of attention was the death of a folk musician named Yu Zhou in February 2008. [see photo at top of page]

It was around 10pm when a police car pulled Yu and his wife Xu Na over as they were returning from a performance of his band, “Xiao Juan and Residents of the Valley”, at the end of January in Beijing.

After a quick search of the couple’s vehicle, the officers discovered the two practiced Falun Gong. They were immediately arrested and taken to Tongzhou District detention center.

Eleven days later, the authorities notified Yu’s family members to come to Qinghe Emergency Center where they found him dead, although they say he had been in good health before his detention.

Pointing to the obstacles imposed by the Chinese authorities before journalists seeking to investigate such cases ahead of the games, a (London) Times reporter received the following response when asking a member of Yu’s band to confirm if he had been killed: “It is not suitable to answer this question. As you know, if I answer it I will be in trouble.”

“Long Term” Implications

As for Yu’s wife Xu Na, she remains in custody and is awaiting sentencing. In April, her family was informed that she had been charged with “using a heretical organization to undermine implementation of the law,” a vague provision of the penal code commonly used to sentence Falun Gong adherents to prison for up to 12 years.

With such long sentences hanging over the heads of those detained and dozens already sentenced to labor camps for several years, a layer of complexity is added to the question of the relationship between the Olympic Games and the recent escalated repression.

The long terms imposed on practitioners suggest that in the case of Falun Gong, the Party’s interest is not only in preventing any form of protest or dissent, however peaceful it might be, from being voiced by Chinese citizens during the games. Rather, it would seem that the leadership has also decided to use the games as an occasion for furthering an eradication policy it has been pursuing since 1999–all the while avoiding international condemnation by attributing the crackdown to the needs of “Olympic security.”

As has been the case in the campaign against Falun Gong more generally, those arrested stem from diverse segments of society. They include professionals such as lawyers, accountants, and teachers, as well as peasants and retired workers. Significantly for adherents and their families, a number of those arrested have been forced to leave small children or elderly parents at home with no one to care for them.

More broadly–like petitioners and civil rights activists being detained– Falun Gong adherents have emerged as a central element of a growing grassroots movement of Chinese people becoming aware of their rights, protesting the regime’s brutality, and asking for greater freedom.

“The government has locked itself into a fictional account that the Chinese population has no interest in human rights and no criticism against the preparation of the Olympic Games,” Nicholas Bequelin, a Hong Kong-based researcher for Human Rights Watch told the Washington Post recently. “Since that’s not the reality and thousands are involved in human rights activities, they have to silence quite a few people.”

As explored in more detail in “Righteous Resistance” later in this magazine, one of the methods adherents have been using to raise awareness is the distribution of leaflets and homemade VCDs about Falun Gong and the persecution of fellow practitioners. In recent years, however, they have added into the mix copies of publications that address rights abuses more broadly, such as the Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party.

The arrest of thousands of people involved in such awareness raising activities is therefore a serious setback, not only for the Falun Gong community, but also for the Chinese people as a whole and for the country’s potential for moving towards a freer society.

But this pre-Olympic purge of Falun Gong does not only bear long term implications for the Chinese. It also leaves cause for reflection to the international community that chose to award the games to a regime like the Communist Party’s.

Given that the Party has used the Olympics as an excuse to further a persecutory campaign against thousands of its own people, should we perhaps be asking ourselves – what dangers might we be imposing on Chinese citizens by awarding an international event to this regime again in the future?