Investigative Report: A Hospital Built for Murder

Tens of thousands may have been killed so the Tianjin First Central Hospital in China could transplant organs for profit

By Matthew Robertson, The Epoch Times | Jun 04, 2017

By 2006, from his base at the Tianjin First Central Hospital, Dr. Shen Zhongyang had performed over 1,600 liver transplantations, boastful Chinese media reports say. Tianjin First, a hospital whose transplant ward he led, was just getting a new, well-funded building courtesy of the local government. Shen had patented his own surgical technique for rapid liver perfusion and extraction, and official transplantation websites were calling him China’s “great transplant pioneer.”

With all the celebration in the Chinese press of the doctor’s life-saving operations, little attention was paid to the sources of the organs he transplanted. Dr. Shen’s career was being built on a pile of corpses—that much was apparent—but the real question was: where did they come from?

The official explanation, that only formally executed prisoners are used, relies for its credibility on the number of transplants corresponding roughly with the number of executions. In Tianjin, that would be about 40 executions a year—a number derived from calculating the city’s population against the national death row total.

But at Tianjin First Central, the number of transplants is off the charts.

Official numbers from the hospital are scarce, but penetrating that secrecy makes clear that Tianjin First Central Hospital, one of the busiest and most acclaimed in the country, for years having enjoyed extensive official backing, transplanted many times more organs than a supply of executed prisoners could support. Moreover, it appears to have transplanted many times more organs than it says it did.

In a detailed study of its activities based on publicly available documents, Epoch Times found sufficient evidence to throw into great doubt, if not demolish entirely, the official narrative of organ sourcing in China. This is simply due to the number of transplants: they are far too high.

That’s a problem for China.

It means that the vast majority of organs transplanted at the Tianjin First Central Hospital—and by extension, other major hospitals around the country—could not have come from executed prisoners. Nor did they come from volunteers in any significant numbers, given that it is only very recently that a voluntary organ donation system has been attempted in China, and it is still in its fledgling stages.

This inevitably raises another question, which the Chinese authorities have found particularly vexing but have never addressed: where did the organs actually come from? What is the secret organ source that in the year 2000 suddenly became the basis for a nationwide expansion of organ transplant capacity, for which the Tianjin First Central Hospital stands as an exemplar?

For years human rights researchers have alleged that the captive population of Falun Gong adherents, a persecuted Chinese spiritual practice, is the likely source. The gaping disparity in the Tianjin case, along with a variety of other circumstantial evidence, adds ammunition and urgency to their claims.

This issue has largely been dodged by luminaries in the international medical community. But the circumstantial evidence bolstering the alternative explanation—organized mass murder of prisoners of conscience using the tools of medicine, in the service of profit, by the world’s most populous nation—continues to grow, and with it frustration among doctors that nothing is being done.

A Surgeon Starting

In the late 1990s, Shen Zhongyang, a liver transplant surgeon, was at a definite ebb in his career: the organ transplantation industry in China was little developed, operations were risky, so willing recipients were few, and organ supplies were limited.

In May of 1994, he rendered Tianjin its first liver transplant after persuading a 37-year-old migrant worker suffering from cirrhosis to undergo a transplant. At the time, transplants were done free of charge for the recipients, largely due to the low success rate.

Years passed with no notable developments, and in 1998 Shen returned from Japan where he had obtained his M.D. Upon return, he spent his own money (100,000 yuan, or $15,000) to set up a small transplant unit at the Tianjin First Central Hospital.

Progress was slow at first: by the end of 1998 his transplant unit performed just seven liver transplants. In 1999, they performed 24.

In 2000, things quickly turned around as a new organ supply abruptly came online. Over the next decade Shen Zhongyang did some of the briskest organ transplantation business in China.

In Tianjin, numbers kept going up: 209 liver transplants by January 2002; and then a cumulative total of 1,000 by the end of 2003, according to a report in Enorth Netnews, the mouthpiece of the Tianjin municipal government.

Tianjin First Central Hospital’s successes are a microcosm of the Chinese organ transplantation system: its operations are opaque; paramilitary ties lurk in the background; organ procurement remains unexplained and rapid, suggestive of a pool of donors waiting to be selected from; and the surgical techniques are consistent with live or close-to-live harvesting from donors.

Doing the Build-Out

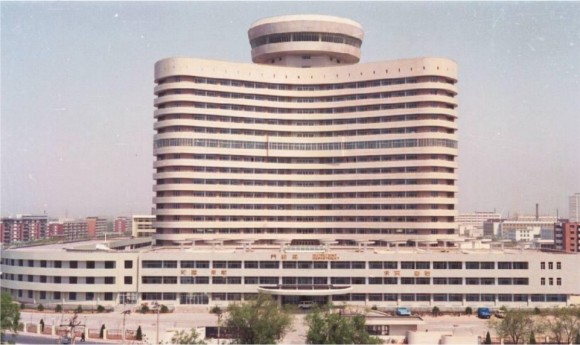

The most significant moment for the expansion of Tianjin First, an apparent sign of confidence of continued abundant organ supply, was the 130 million yuan ($20 million) investment in December 2003 by the Tianjin Municipal Bureau of Health to construct a 17-story (including a ground and two basement levels) transplant building.

Named the Orient Organ Transplant Center, with a 500 bed capacity and floor space of 36,000 square-meters, it was to become a “comprehensive transplant center capable of liver, kidney, pancreas, bone, skin, hair, stem cell, heart, lung, cornea, and throat transplants,” according to Enorth Netnews.

The entire Tianjin First Central Hospital then consisted of an emergency ward, an outpatient center, and the transplant building.

By 2004, while the Orient Organ building was under construction, in order to accommodate demand, Shen’s transplant empire expanded to five branches scattered across Tianjin, Beijing, and Shandong Province. In their official materials, the group claimed to perform the highest number of liver transplants in the world, and the highest number of kidney transplants in China.

The Beijing branch was located in the General Hospital of the People’s Armed Police, the Communist Party’s one-million strong paramilitary force, where Shen Zhongyang served as director of the transplant department.

If one transplant center in China had to be chosen for its notoriety, it would probably be the Orient. The facility became a major headache for Chinese authorities, Western apologists, and the official story behind China’s transplant industry.

Hospital With a History

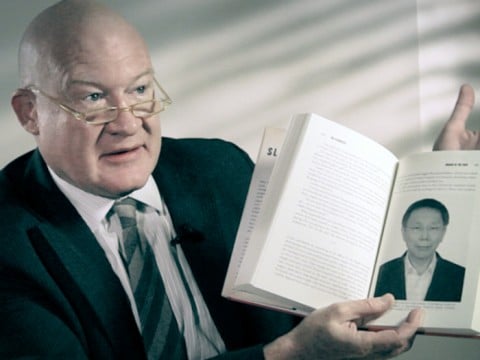

Ethan Gutmann, a researcher whose 2014 book, “The Slaughter,” documents what he says is the mass killing of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience for their organs, described the website that advertised Orient’s services—www.cntransplant.com—as his “favorite party trick.”

“I would speak to a college audience and ask anyone who had any doubts to visit the website on their smartphones,” he said in an interview with Epoch Times shortly after the site was shut down in June 2014.

It was precisely this center that inspired an exasperated letter in early 2014 from the normally deferential international transplantation establishment, rebuking China for flouting recent promises made in Hangzhou to no longer use organs from executed prisoners.

“The Tianjin website continues to recruit international patients who are seeking organ transplants,” the letter co-signed by The Transplantation Society says. “The underlying abuse by these medical professionals and widespread collusion for profit are unacceptable.”

It was a high-profile operation targeting wealthy customers with a premium, very rare product: fresh human organs available at a rapid turnaround, no questions asked.

That a center so large and sophisticated would be built, staffed, equipped, and operated at high capacity for nearly a decade, when China had practically no voluntary donations, has chilling implications, researchers say.

“It means there’s an absolute conviction that you’re going to find donors to supply those organs,” said Maria Fiatarone Singh, a professor of health medicine at the University of Sydney, in a telephone interview.

“In the context of no voluntary donation system, it implies a complete belief that this unethical supply will be huge and continuous, and that there’s a huge profit to make from it.” Singh is a board member of Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting, a medical advocacy group that raises awareness about transplant abuse in China.

But how many transplants did Tianjin First actually conduct?

The Trouble With Numbers

It is extremely difficult to get an accurate handle on the actual number of organ transplants conducted in China over the years, either in aggregate, or even at a single hospital. In a closed society, information of this sort is highly politically sensitive.

China did not even have a national organ transplantation system until recently. It was a Wild West of hospitals competing for business, doing deals with organ brokers, and getting their hands on human supply however they could. Statistical integrity, or any kind of reliable statistics at all, are the least of the victims.

In the United States, finding out the number of organ transplants that take place is simple. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, affiliated with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, maintains a database that can be queried by dozens of criteria. The total number of transplants performed in the United States from January to September in 2015, for example, was 23,134.

Other datasets provide specific hospital information. The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients is able to spit out a report showing detailed transplant information at any given transplant center. The most active in New York state, for example, is the NY Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia Univ. Medical Center. A report with data current as of April 2015 shows that it performed 110 liver transplants in 2013 and 142 in 2014. The 60 page report provides an abundance of information about those on the waiting list, donor types, transplant rates, and more.

Nothing like this information is available on Chinese hospitals—and for good reason: it’s a state secret.

Dr. Huang Jiefu, the Chinese official who interfaces with the rest of the world on organ transplantation policy, was remarkably frank about why numbers are so hard to pin down, in a rare interview with Chinese journalists last year. The interview was part of an intense run of publicity as Huang sought to get out the message (later debunked) that China was no longer using organs from executed prisoners.

“The death penalty is a state secret,” Huang said. “Organs were sourced from executed prisoners. If you know the number of transplantations performed, then you would know the state secret.”

The reporter pressed further, and Huang countered again: “The issue you are talking about is too sensitive. That’s why I cannot tell you that clearly. If you think about it, you will understand. Because the country has no transparency, you don’t know how the organs were obtained; the number of performed transplantations was also a secret.”

But numbers inevitably seem to trickle out from the holes in even the Chinese Communist Party’s formidable propaganda machine.

In the case of Tianjin First Central Hospital, there are several ways of getting them. While the procedure may have a certain monotony about it, let us consider each in turn.

The Official Graph

The first datapoint is simply a graph from a now defunct but archived page belonging to the Orient Organ Transplant Center, showing the cumulative liver transplants from 1998 to 2004. The yearly numbers grow almost geometrically: 9, 24, 78, 129, 272, 289, and 800. These figures, however, are contradicted by figures in other official sources.

The same page advertises the waiting time for a liver transplant as two weeks—unheard of in countries with voluntary donation systems.

Livers are a useful organ for calculating how many executions must have been carried out for transplants, given that they are a vital organ, and a transplantation of a full liver requires a death. Given that executions in China have traditionally been the sole source of transplant organs—whether that has changed is another matter—the question of number becomes significant.

The problem with the graph is that it stops at 2004.

The Pastiche

Another method is to simply look at media reports that provide numbers. In this case, beginning in 2000, the number is 78—same as above. The source is a puff piece about Shen Zhongyang in Science and Technology Daily titled “He brought liver transplant technique to the pinnacle of world medicine.” A later source in 2000 gives a cumulative total of 100.

In 2001 there is no cumulative figure, but the annual total is 109 liver and 80 kidney transplants, the sources being a Chinese medical encyclopedia and news reports.

In 2002 there is no annual figure, but the cumulative is 300, according to a profile of Shen Zhongyang.

In 2003 the cumulative total in Tianjin is 645 (though up to 400 other transplants were performed by the Tianjin First team in other hospitals around China, according to an official news report) and the annual 253.

This is when a budget is approved at the end of the year for the construction of the 17-story Orient Organ Transplant Center.

In 2004, no specific yearly total was published—but the cumulative total stood at 1,000, according to a report on Medical Education Net, a large Chinese online medical encyclopedia.

“He brought liver transplant technique to the pinnacle of world medicine.”

In 2005, no cumulative total was published, but the yearly total sat at 647 (according to an official, laudatory profile of Shen published in 2014.)

In 2006, 655 transplants were recorded, according to an official profile of Shen and a medical paper he authored. In that paper, he said that his center had surpassed the world record of liver transplants maintained by the University of Pittsburgh for 10 years.

And then… radio silence.

Tianjin’s Orient Organ Transplant Center officially opened on Sept. 1, 2006. It remains unclear why, right when the numbers would be expected to jump, annual data dries up.

Incidentally—or not—in March of 2006 allegations began emerging that Falun Gong prisoners were the major source of China’s booming organ trade. Chinese officials dismissed the reports as nefarious propaganda, though never seriously refuted either their argument or inference.

In all available sources, only two numbers appear post-2006: the first, from a speech by Shen Zhongyang to his comrades in the United Front Work Department, a Civil War-era political warfare unit, and the second from a glowing profile of Shen Zhongyang by the Tianjin propaganda authorities.

The Official Profile

The official profile of Shen Zhongyang is published on ttwj.gov.cn. The website is run by the Office of the Tianjin Municipal Government Human Resources Leading Small Group, and serves as the mouthpiece for the Tianjin leadership. “The Tianjin Party Committee and governmentpays a great deal of attention to human resource work,” the About Us section on the website notes.

The profile discusses the incredible success of Shen Zhongyang, his enterprising spirit helping the construction of the Chinese transplant industry, and provides a few transplant numbers.

The early figures are roughly the same as those above, and while after 2006 no precise numbers are given, the profile declares that “for the next two years it became the foremost liver transplant center by volume, and made the Orient Transplant Center the largest scale transplant center in Asia.” It adds that as of the end of 2013, the Center had performed the most surgeries in China for 16 years straight. Some of its techniques had become the “most advanced” in the world.

And, crucially, it provides another number: A cumulative total of “nearly 10,000” liver transplants by the end of 2014, supposedly a quarter of the national total.

Then there is a figure of 5,000 cumulative liver transplants as of the end of 2010, which comes from a speech by Shen Zhongyang posted to the United Front website.

Graphed, the series now looks like this:

Those numbers are already disturbingly high, and extremely difficult to fit into the official narrative of executed-prisoners-as-organ-source.

It is still unclear why annual numbers ceased after the major new transplant center was built, which calls into question whether the neat, rounded numbers can be trusted.

The real number of transplants, according to other records, may have in fact been much, much higher.

There are three indicators of this probability: anecdotes of a booming business in providing organs to Korean tourists; significant transplant figures by Shen Zhongyang’s colleagues; and a guerrilla analysis derived from Tianjin First Central’s own renovation records, dredged from an obscure Chinese database.

Korean Connection

Korean patients began streaming into China, and in particular Tianjin—just a 90 minute flight from Seoul—in 2002, according to Li Lianjin, head nurse at Tianjin First Central Hospital. The hospital had provided organ transplants to over 500 Korean patients between 2002 and 2006, Li said.

Li spoke to Phoenix Weekly, a magazine run by the Hong Kong-based, pro-Beijing Phoenix television station. The article was titled “An investigation of tens of thousands of foreigners coming to China for organ transplants.”

All this activity took place before the Orient Organ Transplant Center came online in September of 2006.

So doctors improvised. One third of their original 12-story building was converted to house transplant patients; the 8th floor of another hospital (the International Cardiovascular Hospital) was also used for Korean recipients; and the 24th and 25th floors of a nearby hotel were also reserved for those waiting. Two nurses were assigned to that location. “Even so, we’re still short of beds,” Li said.

Tianjin was an agreeable destination for Korean organ tourists because in Korea they could typically only receive partial liver transplants from living donors. But in China, they could get whole livers, “and the donor livers are of excellent quality,” the report says.

Procedures were also expedited: foreign patients would simply fax their medical records then fly in. Waiting times were extremely short by international standards. “Originally, patients had to wait about a week. But now, because more and more people have joined the queue, the waiting times are longer. The longest time now is a bit over three months,” the report says.

Three months is still a remarkably short waiting time to guarantee a liver.

The Chosun Ilbo, a large Korean daily newspaper, reported that Tianjin First Central performed 44 liver transplants in one week in December 2004; a family member of a recipient told Phoenix that the hospital performed 24 liver and kidney transplants in a single day.

Patients from other countries were also there: from Japan, Malaysia, Egypt, Pakistan, India, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. The café in the ward on the fourth floor became an “international club,” where patients of different ethnicities met to exchange their experiences, reported Chosun Ilbo.

The report includes this anecdote: “Surgeons at the hospital are busy every day, shuttling between wards and operating rooms. They have no time to greet each other. Every day they mumble the same thing: ‘Today I’m so busy, ten surgeries a day.’ Some doctors spend the entire night in surgery.”

No numbers are given in the report, but it at least confirms that the staff at Tianjin First had been extremely busy leading up to the completion of the new transplant building.

Staffing

The Orient Organ Transplant Center has 110 doctors participating in liver and kidney transplants, among whom 46 are chief surgeons and physicians, and 13 attending physicians, according to the World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong, a network of researchers who performed the monumental task of cataloging the staff of hundreds of hospitals around China.

Media reports, speeches by a select number of Shen Zhongyang’s colleagues, as well as information on the hospital’s own website and other records, indicate many of them had each completed a large number of transplants themselves.

For instance, by 2011, Vice President of the hospital Zhu Zhijun had completed at least 1,400 liver transplants, 100 of which were partial liver donations from living relatives, according to his profile on the website “We Doctors Group,” a directory for Chinese doctors.

As of July 2006, associate chief surgeon Pan Cheng had personally performed over 1,000 liver transplants, and 1,600 liver graft procurements.

Chief surgeon Gao Wei completed over 800 liver transplants after ten years of practice, according to his undated profile on “Good Doctors Online,” another well-known Chinese doctors database.

Associate chief surgeon Song Wenli from the renal transplant department performed around 2,000 kidney transplants; associate chief surgeon Mo Chunbo over 1,500, both according to undated profiles on the same site.

Some of those operations did not result in the killing of a donor—hundreds of donations were from living relatives, for instance (if they were indeed from relatives)—but many of them must have.

As of July 2006, associate chief surgeon Pan Cheng had personally performed over 1,000 liver transplants, and 1,600 liver graft procurements.

Chief surgeon Gao Wei completed over 800 liver transplants after ten years of practice, according to his undated profile on “Good Doctors Online,” another well-known Chinese doctors database.

Associate chief surgeon Song Wenli from the renal transplant department performed around 2,000 kidney transplants; associate chief surgeon Mo Chunbo over 1,500, both according to undated profiles on the same site.

Some of those operations did not result in the killing of a donor—hundreds of donations were from living relatives, for instance (if they were indeed from relatives)—but many of them must have.

If the average total transplant volume of these surgeons was simply extrapolated to the rest of the staff—not necessarily a reliable methodology—the total transplant volume, as of 2014, would immediately be several times greater than the official number of 10,000. It is clear from just a few doctor profiles, however, that the figures are beginning to approach the totals announced by the hospital.

Of course, the doctors whose profiles are available may simply be outliers. Or they may be inflating their records, or have participated in joint operations—all distinct possibilities. In any case, even given drastic discounts, the surgeons’ own organ numbers seem to far outstrip the official ones.

But building records indicate that the transplant volume could be much higher than even that.

Renovating a Transplant Center

Given that the municipal government spent about $20 million (130 million yuan) in building the Orient Organ Transplant Center, common sense dictates that there would be an intended use for it.

But this is China—infrastructure spending can be wasteful, used to prop up local economic figures rather than create productive businesses. Thus, the mere fact of construction and renovation cannot tell us everything.

There is compelling evidence, however, that the new building was put into immediate and extensive use. This comes from the hospital’s own building and renovation records in the China Construction and Remodeling Database, a public resource maintained by a variety of officially-affiliated agencies, providing details of construction and renovation work from across China.

These documents show what seems to have been deliberately hidden in every other available Chinese source: that it was full speed ahead at Tianjin First after the new transplant center came online in 2006.

The key evidence is a 22 page PDF file, available for download after creating a username and password on the site, which discusses the further renovations to the hospital, completed in 2008. The file was published on the database in October 2009, and appears to have been completed in late 2008, given the date in a photograph on page 13. It was prepared by the Tianjin Architecture Design Institute, and its contents refer to the period after the construction of the Orient Organ Transplant Center.

The renovation described in the document is primarily to the main building, the outpatient building, and the emergency ward (the transplant building is left untouched), and included the addition of insulation to the facade “in order to save energy and increase the comfort of patients.” Another floor would also be added to the outpatient building, taking it from three to four stories.

The key line, though, is this: “There is a daily average of 2,000 outpatient services conducted per day; the bed utilization rate is 86 percent; kidney and liver transplantation beds are at 90 percent utilization.”

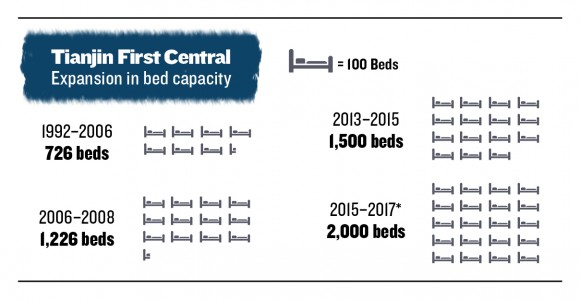

The total number of beds devoted to transplantation at Tianjin First during this period was 500, at the Orient Organ Transplant Center. Total bed count at the hospital sat at 1,226, with 726 originally available. Total floor space was of the Orient building was 46,558 square meters, the document states. Floor plans of Tianjin First appear to verify this breakdown of transplant versus all other activity.

“The bed utilization rate is 86 percent; kidney and liver transplantation beds are at 90 percent utilization.”

Thus, according to these documents, 450 beds were used for transplants, whether livers, kidneys, or other organs.

According to Tianjin’s advertising materials for foreign patients, the total time an organ tourist would expect to stay in the hospital could be between one and two months, depending on the wait time for an organ, and how long it takes to convalesce.

But actual stays could potentially have been much less than the maximum. For instance, the experiences of organ tourists collected by two Canadian researchers in 2007 speak of a mere seven days in the hospital. An assistant head doctor at the Peking University People’s Hospital advises that hospital stays are typically two to three weeks, and a sampling of other mainland Chinese sources also often advise waiting times of just two weeks. It is likely that as technique improved, the hospital stays commensurately decreased.

The average assumed length of stay makes a significant difference to estimates of total transplants that could have been performed. For instance, if an average patient stay was 30 days per transplant, then 5,400 transplants per year may have taken place at the Orient Organ Transplant Center from late 2006 until the end of 2008. If each stay was two weeks, then the amount could be 10,800. If each stay was two months, the total would be just 2,700.

It is impossible to know the actual average length of stay at Tianjin First, but transplant surgeons who reviewed this report considered the range of scenarios to be plausible.

But was this high level of utilization a mere blip in the two years following the opening of the new center? No, according to other renovation reports. It soon became the norm.

The next available datapoint on transplant-relevant bed usage rates at Tianjin First comes from a profile of the hospital on Enorth Netnews, the official Tianjin government mouthpiece, on June 25, 2014.

It says that it had “made progress” across various departments in 2013, and achieved a bed usage rate of 131.1 percent, an increase of 5.7 percent from 2012. (The report does not make clear how a utilization rate of over 100 percent is possible, but it is common in Chinese hospitals to see extra beds wedged between established bedding places, or the hospital could have made available hotel beds for overflow, as they did in years past.)

By 2013 it had also added 300 beds, bringing its total number now to 1,500. The hospital had also adjusted the number of beds allocated to different departments, including the organ transplant center, though it did not specify how many beds were allocated to each area.

It is difficult to know how many of the 1,500 total beds, or 500 Orient Organ Transplant Center beds, were used for organ transplants in 2012 and 2013.

But there is a consistency in the reported utilization rates: 90 percent utilization reported in 2009, and 130 percent for 2013.

Whether that ratio plummeted for four years before soaring—or slowly grew, as the trend of official transplant numbers (though clearly manipulated) indicate—is impossible to tell, though a steady increase seems most intuitive and internally consistent.

Yet more construction took place in 2015 at a newly opened site, including an outpatient service able to process between 6,000 to 7,000 people per day, an emergency center able to process 1,200 daily, an underground carpark able to hold 2,000 vehicles, and a helipad.

The new construction, which began in July 2015 and was scheduled for completion at the end of 2017, will have a total of 2,000 beds. It is unclear how many of them will be devoted to transplants.

Guerrilla Numbers

What numbers emerge from this kaleidoscope of activity?

The hospital would have us believe that when their new transplant center came online, giving them hundreds of additional beds and much more sophisticated facilities, there was no increase in the transplant rate.

The only official data for the post-2006 period is a figure of 5,000 cumulative transplants in 2010, and 10,000 in 2014—a neat, linear increase.

But the facts paint a different picture: anecdotal reports from Korean organ recipients say that occupancy was far more than the hospital could handle; building records showing the need for continued expansion after 2006; and impressive staff resumes showing thousands of transplants from a few of the over 100 doctors.

“…the large number of organ transplants which, apparently, continue to be performed in Tianjin and elsewhere in China, must have an alternative organ source, which needs to be explained.”

With utilization of the 500 beds for kidney and liver transplants at Orient Organ Transplant Center near or above capacity from 2007 to end of 2013, and an average stay of one month per patient, the total number of transplants could have been about 50,000. Of course, only very rough estimates are possible given the many unknowns. Epoch Times produced a table of the range of potential totals.

Any of these figures are far higher than the claimed cumulative total of 10,000 liver transplants over 15 years reported in official sources. That number already presents an awkward dilemma to explain away—but the numbers based simply on bed utilization rates are far higher than any known source of organs is able to explain.

Of course, there is no way to know whether in its building renovation documents hospital staff are simply lying. But it’s unclear what incentive the hospital would have for fabricating the data on its renovation plans, submitted to a national database years after the funds had been committed, and the construction completed, by municipal authorities. Floor space or numbers of beds are tangible infrastructure that cannot easily be falsified, and bed occupancy ratios, from two separate official sources, show the same upward trajectory of high-usage from late 2006 until end 2013.

There are many caveats to these estimates, however, including the fact that the number of executions implied by the bed occupancy rates is not clear. The ratio is likely not 1:1, given that the donation of a single kidney, to a relative, for instance, is neither fatal nor unethical. Tianjin First certainly engaged in this form of transplant activity. Further, one death can yield multiple transplant organs.

Given the multiple variables and vast unknowns, it would be foolhardy to suggest a firm estimate for the number of executions that may have taken place to fuel the business of Tianjin First. But whatever the figure, the implications are the same: the need for a mysterious, unknown organ source.

So, where did the organs come from?

Prisoners Can’t Explain It

China’s only serious source of organs through these years is, according to the official explanation, executed prisoners.

In an interview with China Health News in January 2015, Huang Jiefu, the official who serves as the voice of China’s transplant policy, says: “For a long time China has not been able to establish a national donation system… from the 1980s until 2009, there were only 120 cases of citizen donations. China is the country with the lowest donation rate in the world.”

The number of executions in China is a state secret and no numbers are provided, but estimates have long been made by third party organizations. Those vary from 12,000 to 2,400 per year during the period in question, according to Duihua, a U.S.-based human rights organization focused on China.

“It is true that the source of organ supply are fairly abundant in China compared with that in western countries.”

If the nationwide death penalty was 6,000, for the purpose of analysis, the number of executions taking place in Tianjin would be about 42 (given a population of about 7 million and a proportional distribution of executions.) If the number of executions nationwide was 5,000, there would only be 35 executions in Tianjin.

But many prisoners are not eligible organ donors because of blood diseases, drug addiction, age, and other disqualifying maladies. Procedures around executions involve the local courts and prisons, which have their own relationships with hospitals and doctors, as indicated by abundant testimony from Chinese officials and defectors. The fief-like nature of the Chinese bureaucracy means it’s not as though Tianjin First could have its pick from any execution taking place anywhere in China.

In particular, Tianjin First’s build-up was not an isolated phenomenon: dozens, if not hundreds of other transplant hospitals in China were establishing training programs for surgeons, building new facilities, and promoting their ability to deliver fresh organs to recipients in short order—weeks, or months at most.

In 2014 Xinhua, the state mouthpiece, reported that in past years there were over 600 hospitals in China, vying and contending for organ sources. All of those transplant centers needed organs, too.

And then there are the unnerving advertisements on the hospital’s website, which have since been taken down.

“It is true that the source of organ supply are fairly abundant in China compared with that in western countries,” an archived page on the site says blithely in 2008, in English, obviously targeting foreign transplant tourists.

In the guide for prospective recipients, it outlines the few steps necessary to get a new organ. There’s no waiting list. One simply emails the paperwork, pays $500, and gets on a plane. Step nine is “Staying in hospital to be carefully checked-up, to be well treated while waiting for a matching donor (1 month ± ).”

The website’s landing page in Chinese, on the other hand, advertised a waiting time of two weeks.

In another section, the question is posed: “What are the initial procedures while arriving?” The answer: “Once your data are set, the hospital will start to search all over China for an organ that matches.”

“Just that one line is so shocking,” said Maria Fiatarone Singh, the University of Sydney professor who sits on the board of Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting, in a phone interview. “‘We’ll search the country far and wide for your organ,’” she continued. “Searching for your organ? To search the country for a donor when there is no registry for donors. What does that mean? It means that absolutely they’re looking for the guy they can kill for your surgery. It’s just outrageous. It’s pretty hard to believe.”

In a recent documentary with this very title—”Hard to Believe“—Arthur Caplan, the founding director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Medical Center, explains the contrast in starker terms: “In the U.S., in Europe, you have to be dead first in order to be an organ donor. In China, they make you dead.”

This rapid matching from what appears to be a pool of prematched donors is consistent both with the use of death row prisoners, and harvesting from prisoners of conscience.

But when it comes to volume, death row prisoners simply could not sustain the kind of supply Tianjin needed.

Of course, by itself this is positive proof of nothing—except that the organs had to come from somewhere else.

Recognizing this is the critical first step in any further exploration of the problem: if the organs aren’t from volunteer donors or executed criminals, then they must be coming from somewhere else.

“Anyone who is even remotely familiar with the trends of organ donations worldwide cannot accept the claims of miraculously replacing a huge and well established organ source from executed prisoners within a single year by voluntarily donated organs,” said Dr. Jacob Lavee, the president of the Israel Transplantation Society and director of the heart transplantation unit at Tel Aviv University’s medical center, in an email.

Lavee continued: “If indeed the use of organs from formally executed prisoners has dwindled, the large number of organ transplants which, apparently, continue to be performed in Tianjin and elsewhere in China, must have an alternative organ source, which needs to be explained.”

Into that breach come researchers who have raised allegations of a hidden and largely overlooked mass murder. Coupled with volumes of other evidence, they describe a crime against humanity in which the doctors stand alongside the murderers; the cause of death is the surgery itself, as organs are drained of blood and pumped with cold preservative chemicals.

David Matas, the co-author of a seminal report on organ harvesting from Falun Gong, said in a telephone interview: “What this research does is pose the question; it doesn’t answer the question. But it does put into doubt the established answers that have been given.”

The Forbidden Question

There’s a potential clue about the organ source in one of the many hats that Dr. Shen Zhongyang is found wearing: he appears on the website of the Beijing Armed Police Forces General Hospital, where he serves as director of the organ transplantation department, in full paramilitary regalia. The People’s Armed Police are a domestic standing army of 1.2 million, deployed around the country and mobilized to suppress riots.

The most fundamental obstacle in performing large numbers of organ transplants is a donor source. Given that China had no voluntary, open transplant system, political connections, often mediated through brokers, have been the only way to get bodies.

As Huang Jiefu himself remarked in an interview in early 2015: “Our country is very big. This source of using prisoner organs, this kind of situation naturally would come to have all kinds of murky and difficult problems in it. You know what I’m trying to say? It became filthy. It became murky and intractable. It became an extremely sensitive, extremely complicated area, basically a forbidden area.” He then went on to blame the abuse of organ transplantation in China on Zhou Yongkang, the deposed former security czar. Prisoners of conscience, of course, never came up.

Theories about how Tianjin First Central turned on the organ spigot thus revolve around its political ties, including that of Shen Zhongyang, who became a member of the Communist Party’s faux advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political and Consultative Conference, in 2013. Shen is also a member of the standing committee of the Chinese Peasants’ and Workers’ Democratic Party, one of the eight legal political parties in China that give a window dressing of democracy while stiffly following the Party line.

But it’s his paramilitary title that is most significant for organ sourcing, given that military and paramilitary hospitals are plugged into the security apparatus that hold hundreds of thousands of political prisoners, and are believed to be involved in much of the illegal trafficking in human organs.

A handful of investigators have been tracking the military-organ nexus for years. In his 2014 book “The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China’s Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem,” American journalist Ethan Gutmann marshals a mass of evidence, collected over nearly a decade, to show that practitioners of Falun Gong, a traditional spiritual discipline, have been primary targets for organ harvesting.

Falun Gong, a practice of self-cultivation which involves exercises and moral teachings, has been persecuted in China since 1999, after the Party leader at the time, Jiang Zemin, declared it a challenge to Party rule. By the late 1990s, the number of people practicing it seemed to exceed the membership of the Communist Party.

Hundreds of hospitals around China, like Tianjin First, all saw a dramatic spike in organ transplants in 2000, the year after the persecution began in July 1999.

“There’s no national organ distribution at this point. There’s no organ donation system. The official answer is the death penalty,” says David Matas. “But then you’ve got organ size and blood type compatibility issues, hepatitis in prison, very short waiting times, all of that.”

With no official explanation for the battery of unanswered questions, suspicions, and mounting circumstantial evidence, “you’re pushed back into what myself, David Kilgour, and Ethan Gutmann have been saying,” says Matas. “That it’s prisoners of conscience.” He continued: “The bigger the scale, the bigger the requirement for an explanation, and that explanation is not forthcoming. There’s no obvious other source.”

Gutmann, asked what he thought the likely source of Tianjin’s organs was in a telephone interview, said: “I think the majority of these organs are being sourced from Falun Gong.”

He added: “There has been a large resident population of Falun Gong, of between half a million to a million at any given time within the laogai system through this entire period,” using the Chinese term that refers to the system of labor camps.

“This is the only potential source, numerically, which they could be pulling from. There may be some Uyghur Muslims and Tibetans in there too, though the rates of disappearance are not as high for those communities.”

Gutmann’s interviews of hundreds of refugees found that one in five, and sometimes two in five, Falun Gong detainees were subject to blood testing while in captivity. Those released from labor camps also describe disappearances of those tested. In covertly recorded telephone calls with overseas investigators since 2006, doctors and nurses in China, believing they are speaking to a fellow doctor or the relative of an individual in urgent need of a new liver, have acknowledged that they source their organs from Falun Gong prisoners.

In his book, Gutmann describes first hearing of the medical exams, which one of his interviewees, a Falun Gong refugee, thought little of. “What she described was terrifying and inexplicable—rather than the doctor administering a normal physical examination, it was more like he was already picking over a fresh corpse… I remember feeling an unfamiliar chill as my safe, hedging cloak of skepticism fell away for a moment.”

Tianjin Blood Exams

As in prisons and labor camps around the country, there are anecdotal reports of prisoners of conscience in Tianjin being singled out for blood and urine tests during the period in which Tianjin First Central was at its peak of operations.

These accounts are drawn from Minghui.org, a clearinghouse of first-hand information about Falun Gong in China. Articles on the site are typically submitted by practitioners of Falun Gong, friends, or family members, often documenting their experiences under persecution. The site is widely used by academics and human rights researchers studying the practice or its repression, and is considered a reliable source for insight into the Falun Gong community in China.

Searching Minghui.org for the terms “draw blood,” “physical exam,” and “blood exam,” in Chinese, each paired with the word “Tianjin,” reveals 119, 393, and 69 entries respectively, though some of these may be duplicates.

A typical case, submitted on Nov. 9, 2007, is titled “The persecution I witnessed and experienced at the Tianjin Women’s Prison.” Like many submissions on Minghui, the report is anonymous, for obvious reasons. It says: “The Third Squadron in the prison specifically targeted Falun Gong… the squadron leader of every Third Squadron in each section of the jail called out the Falun Gong practitioners one by one, and gave them blood and urine tests. They didn’t call out criminal prisoners. The squadron leader said it was because they wanted to look after the Falun Gong prisoners.” The prison is a little over 30 minutes away from the hospital.

The author, reflecting back on the experience, writes: “I still wonder where those practitioners who disappeared ended up.”

Other cases of blood tests are reported at the Qingbowa Re-education Through Labor camp. Qingbowa is a 23 minute drive from Tianjin First. The Shuangkou Re-education Through Labor is another camp in which, according to reports on Minghui, Falun Gong practitioners report having their blood tested while in detention. Shuangkou is also about a 30 minute drive from Tianjin First. Falun Gong practitioner Hua Lianyou reports having her blood taken in June 2013 in the Binhai Prison, which is about 45 minutes from Tianjin First. Xu Haitang, a practitioner of Falun Gong, reports having her blood drawn in June 2006 at the Banqiao Women’s Labor Camp, which is about 90 minutes away.

Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting, the Washington, D.C.-based medical advocacy group, conducted its own preliminary analysis on these reports of blood tests on Minghui, writing: “In screening of the survivor reports it was noted that medical exams were not unique occurrences. While single cases as outliers might lack significance, this data reveals a large number of victim accounts that are not isolated instances, and suggests a systematic use of various medical exams imposed upon detained Falun Gong practitioners.”

Of course, none of this is proof that the blood tests were for the purpose of blood matching for organ transplant.

But it is also true that the actual reason for blood and urine tests is unclear, and might otherwise be confusing: the incarcerated individuals are, after all, in prison due to a campaign, led from the highest levels of the Communist Party, to eradicate their belief system. They are typically subject to torture, electric shocks, and beatings in detention, in an attempt to have them renounce their beliefs. Falun Gong had been slandered in the state press, and adherents to it incited against, dehumanized, mocked, and declared to be enemies of the state. Thousands of deaths from torture have been reported, and no investigation or punishment takes place because of the state-sanctioned nature of the campaign. So why would prison officials be extracting blood for the benefit of the captives?

It’s this context that has led analysts to believe that the blood tests and disappearances in captivity of Falun Gong practitioners, along with the transplant boom that took place soon after the persecution began, are most likely explained by large-scale organ harvesting.

The Awkward Silence

Even if the international medical community wished to refrain from concluding preemptively on a massive crime against humanity, one might expect at least a demand for further attention and investigation into just where the organs are coming from, and the extent to which prisoners of conscience have been targeted. It would, after all, constitute one of the most disturbing mass crimes of the 21st century.

Indeed, a number of respected organizations and individuals have made clear that they see a serious problem, and that the idea of harvesting from Falun Gong is not to be relegated to the realm of science-fiction conspiracy theory. The United Nations Committee Against torture in 2008 said: “The State party should immediately conduct or commission an independent investigation of the claims that some Falun Gong practitioners have been… used for organ transplants and take measures, as appropriate, to ensure that those responsible for such abuses are prosecuted and punished.”

Arthur Caplan, the ethicist at New York University’s Medical Center, lent his name to a 2012 petition calling on the White House to “Investigate and publicly condemn organ harvesting from Falun Gong believers in China.” In an interview at the time, he said: “I think you can’t stay quiet about killing for organs. It’s too heinous. It’s just too wrong. It violates all ideas of human rights.”

The recent documentary film “Human Harvest,” which directly addresses the question of harvesting from Falun Gong, won a prestigious Peabody Award in 2014, the broadcast equivalent of a Pulitzer Prize. The awarding of a Peabody requires the unanimous support of the 17 board members, who in their summary of the documentary described a “highly profitable, monstrous system of forced organ donation.”

Some countries, including Israel and Taiwan, have adopted legislation aimed at preventing their citizens traveling to China to receive organs, after the reports of harvesting from Falun Gong emerged.

All this makes the reaction of some of the key players in the international transplant scene—the kind of individuals whose imprimatur would lend sufficient public heft to the allegations as to prompt broader international censure and calls for investigation—all the more jarring. They have been uncurious about the question of crimes against humanity, adopting instead a complaisant stance, part of Kissingerian-styled bid to help the project of China’s organ transplant reform.

Dr. Francis Delmonico, the former head of The Transplantation Society and previously the key international liaison with China on transplant issues, wrote in an email: “My only comment is to encourage the assessment of the Tianjin First Central Hospital to report verifiable data.” The word “only” had been put in bold.

Doctors like Jeremy Chapman, the Sydney-based former head of The Transplantation Society, and Dr. Michael Millis, a liver surgeon at the University of Chicago medical school who has worked closely with Chinese officials, have also evinced little interest in pursuing the tough questions. When pressed about potential Falun Gong organ sourcing, Millis remarked in an interview with Martina Keller, a journalist with the German magazine Die ZEIT, “That is not my sphere of influence. There are many things in the world that are not my focus or interest.”

“This kind of curiosity matters. First, because truth matters; moral hazard matters; human rights matter; and the lives of the exploited, even if dead, matter. They have a moral claim on us.”

The current head of the The Transplantation Society, Dr. Philip O’Connell, and the World Health Organization’s liaison to China on organ transplant issues, Dr. Jose Nuñez, did not respond to emails. The WHO’s Guiding Principles on organ transplantation require that the entire organ transplantation process be transparent and open to scrutiny—yet WHO officials have done little to make such public demands on China.

Responding to the relative dearth of attention afforded the question of the missing organs by doctors, Kirk Allison, director of the Program in Human Rights and Health at the University of Minnesota, wrote in an email: “This kind of curiosity matters. First, because truth matters; moral hazard matters; human rights matter; and the lives of the exploited, even if dead, matter. They have a moral claim on us.”

Dr. Lavee, the respected Israeli heart surgeon, wrote in an email: “I feel embarrassed that my colleagues worldwide do not feel, like me, the moral duty to request that China open its gates for an independent, thorough inspection of its current transplant system by the international transplant community.”

He added: “As a son of a Holocaust survivor, I feel obliged to not repeat the dreadful mistake made by the International Red Cross visit to the Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp in 1944, in which it was reported to be a pleasant recreation camp.”

Updates on Feb. 13, 2016: The sources of official data on cumulative liver transplant figures were clarified: the figure of 5,000 as of the end of 2010 came from a speech by Shen Zhongyang on the website of the Communist Party’s political warfare unit, the United Front Work Department, not from the profile of Shen on the official website of the Tianjin municipal government. The latter source provides the figure of 10,000 cumulative liver transplants as of 2014. Further identifying information was provided about the 22-page document from the China Construction and Remodeling Database, which was used for bed occupancy data on kidney and liver transplants. Further information was provided about the average stay for an organ recipient at Chinese transplant centers, which led to a different range of estimates for the cumulative number of transplants that were potentially performed. A link was provided to a spreadsheet which tabulates this range of numbers, and a graph added showing the projected potential cumulative transplant numbers given the assumption of a one month stay, counterposed with the official data. A paragraph that referenced Shen Zhongyang performing multiple liver transplants for a single patient was removed, because there is only one publicized instance of Shen doing this, and it cannot therefore add materially to the number of transplants that were performed. A different way of searching Minghui.org—directly in the site’s search interface, rather than via a Google site search—was used, and a range of other terms, not just “blood test,” was used. This provided a lower but more accurate estimate of the number of blood or physical exams that took place in labor camps around Tianjin. The article’s original translation of the Chinese term “抽血” as “blood test” was changed to “draw blood,” which is more accurate.

The original article from The Epoch Times can be viewed here: http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/1958171-china-hospital-built-for-murder/