Falun Gong Looks Forward to a New China

After 17 years, the persecution of this spiritual discipline appears to be slowing, and its practitioners are looking to what comes next

By Matthew Robertson, The Epoch Times | Jun 08, 2017

At the time of the 1989 pro-democracy protests in China, Wang Youqun was just starting his doctoral thesis on the theoretical rift between Josip Tito’s Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.

The 1980s were a decade of relative freedom in China—the Cultural Revolution was over, the country was being rebuilt, and its people were thinking for themselves about what sort of nation they wanted. At the same time, the social and political problems caused by a corrupt, entrenched communist elite were difficult to ignore.

Like the idealistic students in Tiananmen Square, Wang also wanted to do something about the rampant corruption in China. But he kept his head down and decided to attack it from the inside: by working in the Chinese Communist Party’s internal disciplinary commission.

He eventually became a key lieutenant to powerful leader Wei Jianxing, head of the Party’s internal investigatory unit and a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, the Party’s top echelon, accompanying him to top secret meetings and drafting his speeches.

Through the 1990s, Wang also began taking up traditional Chinese energy practices, called qigong, that were then popular around the country. In 1995 he began practicing Falun Gong, which was quickly becoming the most influential of the qigongs. People were attracted by its moral teachings and the improvements in health that practitioners often experienced.

Wang hardly knew that he and his new faith would soon be targeted for persecution, becoming the Party’s new No. 1 enemy.

Before the decade was through, Wang had been stripped of his position of privilege, humiliated in front of his colleagues, held in solitary confinement, and subjected to high-pressure interrogation.

The rise and fall of Wang Youqun has closely mirrored the fate of Falun Gong in China: first lauded by the state, then vilified and savagely attacked.

The question he now asks—24 years after Falun Gong was first taught to the public on May 13, 1992, and 17 years after the persecution began—is this: Will there be an Act Three?—a revival of the practice in China and a vindication of the tens of millions who have persisted in their faith?

Politics Is Personal

Falun Gong is a traditional Chinese practice of self-cultivation—a term that refers to transforming the self through moral discipline and special meditative exercises. Practitioners seek to adhere to the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance in daily life, and reflect on the difficulties that befall them as opportunities for internal betterment. It includes five gentle exercises.

Since July 20, 1999, the Chinese Communist Party has been engaged in an obsessive campaign to eliminate the practice. It has had much more trouble with this than expected. The orders were given by former paramount leader Jiang Zemin, who appears to have been personally affronted by the popularity of the Falun Gong way. “Can it be that we Communist Party members, armed with Marxism, materialism, and atheism, cannot defeat the Falun Gong stuff?” he wrote in a letter distributed to top Communist Party members.

This unleashed the largest security mobilization and human rights catastrophe in China since the Maoist era. In the classic style of a Mao-style mass movement, practically everyone in society was inundated with anti-Falun Gong propaganda and expected to declare their stance for or against it. Students were forced to sign a piece of paper identifying the practice as a “deviant religion” on their first day of school. Practitioners were isolated, struggled against, jailed, and tortured.

Top Party leaders, officials, and former officials were not left out. Many had family or relatives who practiced, and they were also regarded as enemies overnight.

It’s for this reason that many practitioners think of the campaign against them as a kind of second Cultural Revolution. The first mass political movement is widely understood in China and abroad, but the second is not. The targets of this campaign are still in the shadows, because they are still considered the enemy.

The Party continues to treat practitioners as pariahs in China, and this official attitude has leached through to how the Falun Gong story is told—or rather, not told—in the West.

Many who focus on Chinese affairs for a living have little sense of the stories and struggles of people like Wang Youqun, and therefore often fail to see the significance of the anti-Falun Gong campaign, and the extent to which the Falun Gong faith community remains a serious social and moral phenomenon in contemporary China.

Wang, at least, appears to have made his voice heard.

For nearly a decade, he wrote letters to retired cadres and top Party leaders, defending Falun Gong, declaring its innocence, and condemning the power-hungry Jiang Zemin. He would pen these letters from the same state-supplied apartment in Beijing, which he was allowed to remain in for nine years after the persecution started. Wang attributes this remarkable instance of leniency to the protection of his own patron, Wei Jianxing.

As well as being head of the Party’s disciplinary apparatus, Wei was on a committee that oversaw the security system. In 1998, Wang personally delivered to Wei, over lunch, a letter about the benefits of Falun Gong, requesting that he do something to head off the troubling pressure being applied to it by ideological hardliners.

Wang was the first member of the Party to be expelled due to his Falun Gong ties. “All central-level work units in Beijing had a meeting in which my name was read out.” This is a classic technique of political struggle in communist history, in which wayward Party members are singled out and made into “negative examples.”

Wang was put under about four months of confinement, monitored 24 hours a day, and subjected to marathon interrogation sessions. In 2008—when he had written one letter too many—he was convicted of “using a heterodox religious organization to undermine implementation of the law” and sentenced to four years imprisonment. Prior to actually entering the Qincheng Prison in Beijing, he had already spent over 532 days in detention centers.

In New York since early 2015, he continues his letter-writing campaign, dispatching missives to retired cadres and addressing Party leader Xi Jinping in detailed editorials.

Wang maintains that his case is instructive for what it demonstrates about the personal element in Chinese politics. That his patron was able to protect him from the worst of one the Party’s most vicious political movements speaks to the outsize role of personalities in determining how and which policies are formulated and implemented.

“China is a rule-of-man society, not a rule-of-law society,” Wang said.

While it is common among Western researchers to emphasize the institutionalized nature of the anti-Falun Gong campaign, and its policy continuity over three Party leaders—Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and now Xi Jinping—for Wang, grasping the significance of the personal element is key.

“The core of the matter is Jiang Zemin. Few others really had bad thoughts about Falun Gong.”

And this is what he hopes will become a chink in the armor of the Communist Party, and allow the possibility of real change.

New Broom

There are signs, in fact, that such a shift is already underway. While observers have been focused on the manifold ramping up of repression since Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, the changes behind the scenes, in the sectors of the Chinese political apparatus that touch on the persecution of Falun Gong, have been tectonic.

These began with the arrests and prosecutions of Zhou Yongkang and Bo Xilai, the former security czar and his presumptive replacement, which took place from 2012 to 2015. The arrest and jailing of either of these individuals—in particular Zhou—had widely been considered inconceivable before it actually took place.

Zhou was without doubt one of the most powerful men in China, perhaps even more than the actual top leader, given his untrammelled control over a security apparatus whose budget exceeded that of the armed forces, and whose power had been able to grow unchecked for more than a decade.

Both Zhou and Bo were moved up through the system by their patron, Jiang Zemin, and both of them eagerly implemented his anti-Falun Gong policies before they were brought into the central government by Jiang as a reward.

In Sichuan Province, for instance, Zhou, as provincial Party secretary, spoke regularly about the need for all agencies to join the “fight against Falun Gong.”

According to respected Chinese journalist Jiang Weiping, whose biography of Bo Xilai landed him in jail, Bo was told by Jiang Zemin, “You must show your toughness in handling Falun Gong. … It will be your political capital.” Jiang Weiping now lives in exile in Canada.

The labor camp system, one of the key tools for holding practitioners, was also abolished in late 2013. This apparatus was the most convenient means for persecuting Falun Gong, and Chinese media reports at the time cited the enormous internal resistance to its abolition being due to the large number of Falun Gong detainees in them. (Other, less formal means of detention, have since been used instead.)

Even Li Dongsheng, the head of the 610 Office—the top-level secret Party task force set up to oversee and coordinate the anti-Falun Gong campaign—has been purged. Prior to his removal Li rarely publicly wore the title of the secret agency; he was instead called vice minister of public security, his formal state role. But in the announcement of his purge, it was the 610 Office title that was mentioned first.

“I think there is a genuine ambiguity about what it all means,” said Andrew Junker, a sociologist at the University of Chicago who is writing a book about Falun Gong, in a telephone interview. “But it looks like there is room for the possibility of a change in policy.”

He added that the developments “are really a curious thing, and that decisions could potentially lead to a reform moment around the policy on Falun Gong. …” “What does it mean that Li Dongsheng was removed from power? Is that a coincidence? Is it factional battle, or is it about Falun Gong, too? At least it’s ambiguous, and that leaves room for interpretation.”

In an oblique move, Zhou Yongkang has even been blamed for the forced harvesting of prisoners’ organs.

In a 2015 interview with the pro-Beijing Phoenix Television, Huang Jiefu, the spokesman for China’s transplant system, remarked: “It’s just too clear. Everyone knows the big tiger. Zhou Yongkang is the big tiger; Zhou was our politics and law secretary, originally a member of the Politburo Standing Committee. … So as for where executed prisoner organs come from, isn’t it very clear?”

He added, speaking about the organ transplantation industry: “It became filthy. It became murky and intractable. It became an extremely sensitive, extremely complicated area, basically a forbidden area.”

To be sure, Huang’s comments made no mention of Falun Gong. But the explicit call-out was highly unusual, and leaves open the possibility that if its hand is forced, the Communist Party may look to pin the crimes on Zhou and his cronies.

Public promises about the cessation of using prisoners’ organs for transplants, and recent reconfigurations in the management of military hospitals—believed to be the primary location of organ harvesting—are two other sly indications that a clean-up and cover-up of organ harvesting of Falun Gong may be underway.

The charge of systematic, industrial-scale organ harvesting has always been the most extreme, incredible, and volatile of the crimes the Party is believed to have committed against Falun Gong practitioners. Revelations of a large-scale medical genocide could have enormous repercussions for the legitimacy of the Communist Party inside China and internationally.

In the Spotlight

Over the last year or two, the Falun Gong story has received the most serious international attention than at any time since the persecution began in 1999. Most notably, evidence that mass organ harvesting is indeed happening has made the greatest progress in reaching an international audience.

The clearest sign of the slowly increasing international acceptance of the reality of this crime is a number of public acknowledgements over the last year, including the introduction of a congressional resolution and two major awards—the Peabody and the AIB Award—given to the documentary “Human Harvest,” a film directed by Leon Lee, a filmmaker in Vancouver.

The Peabody Award is often described as the broadcast equivalent of a Pulitzer Prize and requires the unanimous support of a distinguished panel of judges. They called the film an “exposé of a highly profitable, monstrous system of forced organ donation.”

“As Falun Gong practitioners have told their stories by different means, people have come to learn about the persecution, and have peacefully resisted the persecution,” Lee said in a telephone interview.

Lee is just one of a new crop of storytellers who is giving an account of the crimes committed against practitioners of Falun Gong in a way that resonates with educated, Western audiences.

Many of the practitioners who have come as refugees to Western countries were socialized in China, and like democracy activists of an earlier generation, sometimes employ a mode of communication unfamiliar to those in their new homes.

Moreover, partly because Falun Gong is not an institutionalized practice—it has no membership, finances, or central organization—it lacks a formal public relations apparatus, and relies on groups of volunteers to do the work of lobbying congressional representatives, preparing updates, holding events, or talking to reporters.

But the eruption onto the scene of Anastasia Lin, a practitioner of Falun Gong who was awarded Miss World Canada 2015 last May, suddenly raised the practice’s profile worldwide.

After attempting to attend the beauty pageant being held in Sanya, China, she was rejected at the Hong Kong airport, triggering a global media storm. In interviews, speeches, and talk-show appearances, Lin, who was born in China but mostly grew up in Canada, projected an unconventional, fresh new face for the practice.

Lin is neither a spokesperson for Falun Gong nor an expert on the topic, but the novelty of her case thrust her into the spotlight, and she was featured in dozens of high-profile media appearances, including a front-page story in The New York Times. She was described as “charismatic, canny, and media-savvy … a public-relations nightmare for Beijing.”

In a recent interview, Lin remarked that in her encounters with journalists and researchers, she encountered a general lack of familiarity with the practice. Some didn’t know, for instance, that Falun Gong has no actual formal organizational structure, or what its core tenets are. “It’s not their fault. Practitioners haven’t run a great PR campaign. Being unfamiliar is OK—so now let’s get familiar.”

Many Chinese adherents came to the West as refugees, and so “use very Chinese ways,” she said. “It doesn’t work here.” There are, of course, many Westerners who practice Falun Gong, “But they have full-time jobs. They don’t spend all day on this issue.”

Nevertheless, Lin said she had heard from friends that the public image of Falun Gong had shifted, and that it had somehow become more familiar after her pageant imbroglio. Lin’s emergence is the most high-profile instance of a Falun Gong mainstream crossover, and her own persona—ardent, bubbly, righteous—served to disrupt brittle stereotypes.

A Reduced Appetite for Killing

Ultimately, of course, key questions about the global posture of Falun Gong come down to how practitioners are faring in China, and what the status is of the anti-Falun Gong campaign there.

The picture is mixed. For the past year, large numbers of practitioners in China have submitted legal complaints against Jiang Zemin, describing how the persecution he initiated has caused financial devastation, torture, or the loss of life of family members. In Northeastern China in particular, ground zero of the persecution, the response to these legal complaints has been brutal.

Last September in Liaoning Province, as punishment for filing a complaint against Jiang, police officers pushed Falun Gong practitioner Wu Donghui down a flight of stairs at her workplace. Later, they extorted 15,000 yuan from her father (US$2,300, or about 25 percent of the average annual wage for an urban worker in China).

In January, Chen Jing of Jiamusi, a city on the Siberian border, was taken into custody and tortured: She was bent over backward, had her feet and hands tied together, and was then hoisted up on a rope tied to a heating pipe.

This excruciating torture was repeated numerous times in an attempt to have her incriminate her fellow practitioners. A police officer then broke all her fingers on one hand, according to an account on Minghui.org, a clearinghouse for firsthand information about the persecution in China.

But these instances must be counterposed with experiences like those of Sheng Xiaoyun, the mother-in-law of YouTube celebrity Ben Hedges, whose program about a Westerner’s view of China is broadcast on New Tang Dynasty Television.

Sheng, also in northern China, was neither beaten nor tortured. Instead, the 10 days she spent in captivity after filing a legal complaint against Jiang Zemin seemed like a pro-forma affair: She was allowed to perform Falun Gong exercises while in detention, and even recite Falun Gong’s teachings. When she was released, her confiscated computer was actually returned to her.

“Police treat Falun Gong practitioners better these days,” she said in a telephone interview. “They know that practitioners are good people who have been mislabeled. Sometimes they don’t try to stop you if you tell the truth about Falun Gong. There are police who know the truth.”

Others have been able to file their legal complaints against Jiang without any harassment. A decade ago, the attempt to do so was a death sentence.

“The Party hasn’t really put down a clear policy from the top to prohibit this activity,” said Xia Yiyang, senior director of policy and research at the Human Rights Law Foundation. This explains the widely varied treatment experienced by the plaintiffs.

In the past, these cadres were largely left to run rampant because the priority was persecution, not good government. “Now the main characters in this chain of command are no longer protected. This is a big change.”

Of course, the official policy against Falun Gong has not changed. And practitioners do not hope or expect a “pingfan,” Chinese political nomenclature meaning political rehabilitation. (The term is considered problematic for the manner in which it tacitly gives the Communist Party the prerogative to decide which groups are legitimate and which are not.)

Instead, practitioners expect that the vindication of their creed will only take place when the Communist Party collapses.

They’re at once engaged in an attempt to help the Chinese people prepare for this eventuality, while also encouraging Xi Jinping to push the process along and secure his own position in history as part of the bargain.

Post-Persecution China

The Falun Gong community has, since 2005, been engaged in an attempt to peacefully undermine the very basis of Party rule: the support for the Chinese Communist Party in the hearts and minds of Chinese. This was Falun Gong’s response once it became clear, in about 2004, that any form of coexistence with the regime had been made impossible.

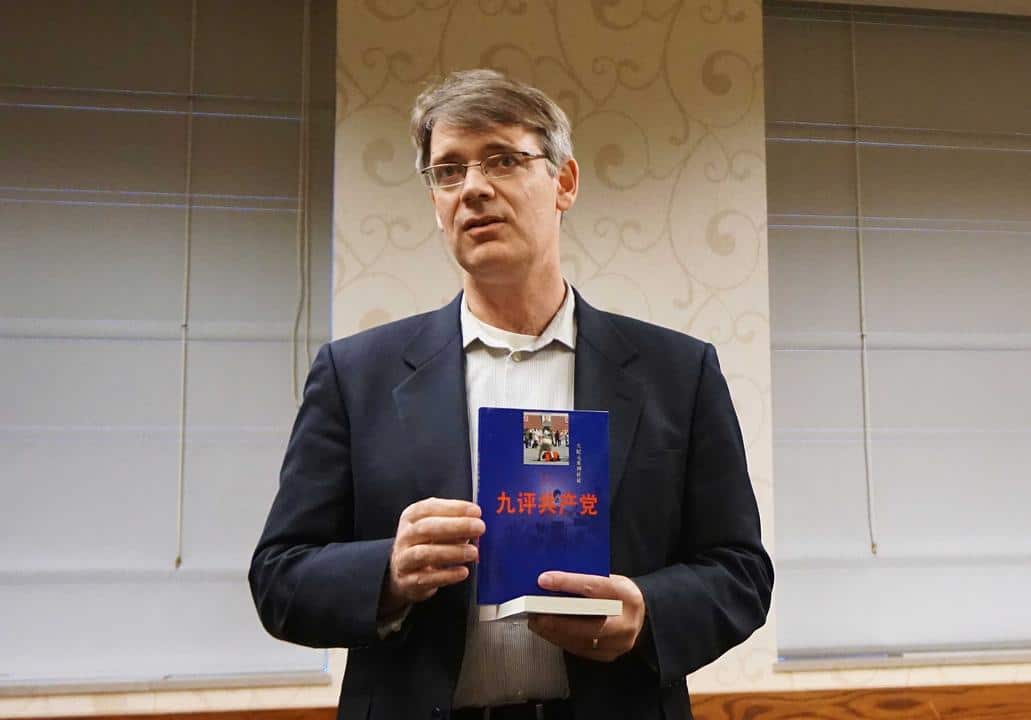

The most concrete articulation of this ethos is the “tuidang” movement. Tuidang means quit the Party in Chinese, and the movement calls on Chinese people to make a private stance against the regime by adding their names to a roster of those who renounce the Communist Party and its affiliated organizations. The tuidang center, whose database is hosted on servers run by the Chinese-language version of this newspaper, has registered over 200 million renunciation statements so far. Those who may renounce include not only formal Party members, but any Chinese person.

“It’s not a political movement where we want people out on the street demonstrating,” said David Tompkins, a spokesman for the organization. “It’s about people breaking with the years of indoctrination they’ve grown up with under the Communist Party, to rid themselves of the Party.”

“Tuidang is a vision of a new China that Chinese people can have and a new future, really, but it’s without the Communist Party,” he added.

He said that this year there have been many more instances of those quitting using their real names rather than pseudonyms. “The voices of dissent are growing stronger and less fearful of oppression or reprisal from the regime.”

Ever since Falun Gong made a stand against the creeping repression against it in 1999, it has in a fundamental way, without even meaning to, acted in such a way as to simply negate some of the most basic axioms of Party control of China.

As David Palmer, a professor of Chinese religion based in Hong Kong, wrote in his book “Qigong Fever,” “Falun Gong projected the image of a powerful alternative order, capable of mobilizing the masses, and which was not afraid of the Chinese Communist Party.”

On April 25, 1999, three months before the official repression began, approximately 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners had gathered in Beijing near the Party compound of Zhongnanhai to ask for a safe and legal environment for their practice.

Explaining this, Palmer wrote: “Until today, political authority in China is only partially exercised through a machinery of control and repression, and more so through the subjective perception and fear of its power. The reinforcement of such impressions, through propaganda and the spectacular performance of power, is thus crucial. The Zhongnanhai demonstration threatened to shatter the fear of the people and to transfer symbolic power onto Falun Gong.”

The vision of Falun Gong’s vindication isn’t the maudlin wish to return to the embrace of the Party, as even some of the most hardened democracy activists of previous generations sometimes hoped for. In the view of practitioners, there can be no reconciliation with the Party—but only a new China without it.

Given the Chinese economy’s brewing troubles, what some describe as a crisis, and the unprecedented divisions in the Communist Party, a potential for significant change seems inevitable—and it’s something that the Falun Gong community is ready for.

Wang Youqun, in his interactions with high-level Party cadres, senses that many in the regime have been left with a deep impression of practitioners’ staunch resistance over the past 17 years.

Their sacrifice for their faith is a stark contrast to the self-preservation and materialist pursuits of Chinese officials. “Nobody believes in Marxism anymore,” Wang said. “Nobody believes in the Party. People just look out for their own interests.”

The idea that the persecution of this practice is no longer in vogue politically, or even that it might end, frightens some in the security apparatus. They want to know which way the wind is blowing, and Xi Jinping’s purges of the system for persecuting Falun Gong don’t help put their minds at rest.

“This is a totalitarian system, with centralized control and surveillance. In each sector, the power of the official in charge is total. But as soon as the top person changes, everything can change,” Wang said. “If Jiang Zemin dies, the persecution policy might totally change.”

The original article from The Epoch Times can be found here: http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/2062536-falun-gong-looks-forward-to-a-new-china/